Memphis to Manchester: Stax Crosses the Pond

By the mid-’60s, Stax Records had proven it wasn’t just a regional powerhouse—it was a cultural force, thanks in large part to the magnetic Otis Redding. But as the British Invasion raged on, the Memphis label wanted more than just American acclaim—it wanted staying power across the Atlantic.

Stax to Host the Beatles. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

• STAX TO HOST THE BEATLES… OR NOT •

Sensing the label’s rising influence, Beatles manager Brian Epstein reached out to Stax co-founder Jim Stewart in the spring of 1966. The Beatles, fresh off the release of their soul-tinged Rubber Soul, were planning their upcoming U.S. tour and had a bold idea: they wanted to visit Stax Records. It wasn’t just a casual detour—it was a sign that the Fab Four were eager to steep themselves in the raw, unmistakable sound of Southern soul, right at the source.

By March, Estelle Axton—Stax’s co-founder and spiritual heartbeat—welcomed Epstein to Memphis, giving him a personal tour of the city’s soul scene. It wasn’t just a meet-and-greet. Behind closed doors, plans came together fast.

They circled a date: April 9, 1966.

That’s when Epstein would return—with the Beatles in tow—to cut a single and record an album at Stax. Jim Stewart would take the helm as producer, Steve Cropper would handle arrangements, and Atlantic Records’ legendary Tom Dowd would oversee the sessions. Memphis was about to play host to a musical collision like no other.

Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

For Steve Cropper, the pressure was dialed up—he couldn’t read a note of music, yet he was expected to arrange songs for the biggest band in the world. “I know enough about music to know what it is and I do a few sessions in Memphis for some other companies where I have to read,” Cropper said years later. “If I have to, then I can sit down and do what I have to do as long as it’s simple and not complicated. I’m not real fast at it. But in my work, in the arrangements, I seem to get a better feeling with head arrangements.”

As plans quietly fell into place, Estelle Axton had one job—keep it all under wraps. She moved through the halls of Stax like a secret-keeper, whispering to staff and artists alike: Not a word. The world’s biggest band was coming to Memphis, and the stakes couldn’t be higher.

But on the morning of March 31, the silence was shattered.

Splashed across the front page of the local paper, just beneath a headline about a Klansman surrendering to authorities, was the bombshell: “Beatles to Record Here.” Estelle had confirmed it. The worst-kept secret in Memphis was out.

The paper had to spell it out for readers who didn’t even know their city was home to a global music powerhouse. It described Stax as a recording studio that had found “unusual success with Negro artists.” Suddenly, East McLemore Avenue—where many white Beatles fans had never dared to go—became ground zero for the biggest cultural crossover in modern music.

The Beatles. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

And then, just as the gears were turning and the dream seemed within reach, the call came: the Beatles had to cancel.

The album that might’ve blended Liverpool pop with Memphis soul—what could’ve been the greatest transatlantic session in music history—would now be recorded in London. That album, Revolver, still bore traces of the Southern soul sound, with its jangling guitars, brassy flourishes, and experimental swagger. It was a psychedelic leap forward for the Beatles, but Memphis was missing from the liner notes.

Still, the message was clear. Stax had reached far beyond Memphis. It had helped shape what music could be—not just in America, but across the globe. If the Beatles wouldn’t come to Soulsville, U.S.A., then Soulsville would find its way to them.

• THE STAX/VOLT REVUE ELECTRIFIES EUROPE •

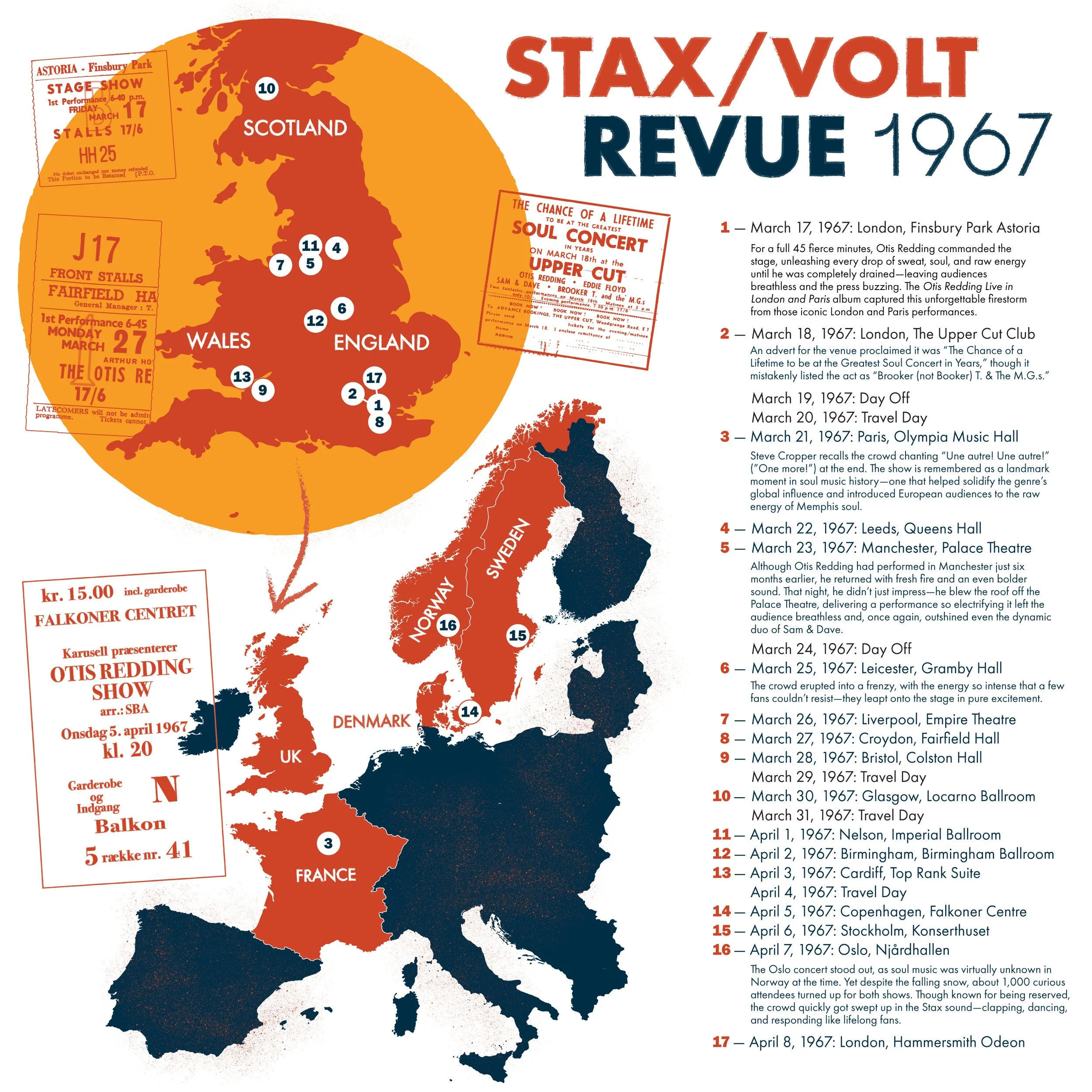

By 1967, Stax was ready to go global. Inspired by Motown’s triumphant 1965 tour of Europe, the label began mapping out its own musical invasion. The Stax/Volt Revue—a powerhouse lineup of the label’s biggest stars—was booked for a whirlwind European tour, set to launch on March 17 and return April 9. The date was no accident: it marked exactly one year since the Beatles were supposed to visit Soulsville, U.S.A. Now, it was Stax’s turn to cross the Atlantic.

When the artists landed in London, they were stunned by the reception. British teens lined the airport, waving homemade signs and screaming like it was Beatlemania in reverse. To the artists’ amazement, the Beatles themselves had arranged a fleet of Bentley limousines to chauffeur them to their hotel—an unmistakable gesture of admiration and respect.

The Revue opened and closed in London, but along the way it shook up cities throughout the United Kingdom, Paris, Copenhagen, Stockholm, and Oslo. For many of the performers, it was their first time leaving the U.S., their first taste of new languages, strange menus, and foreign customs. But more than anything, it was their first time feeling truly seen—greeted not just as entertainers, but as stars.

The soul of Memphis had touched down in Europe—and the crowd was more than ready.

Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

Otis Redding and Sam & Dave weren’t just performers—they were rivals in the purest, most electric sense. Their legendary showdown played out city after city on the Stax/Volt Revue, a nightly tug-of-war for soul supremacy that left crowds delirious. Sam & Dave hit the stage like a lit fuse, detonating each set with wild choreography and gospel-soaked fire, daring Otis to top them. And he had to—many of the posters billed it as The Otis Redding Show.

Backstage, Redding, billed as “The Sensational Otis Redding” throughout Europe, watched with a mix of anxiety and determination. Unlike the gospel-infused theatrics of Sam & Dave, Redding’s style—more sensual and polished—had been shaped by years on the Chitlin’ Circuit and his apprenticeship with James Brown. He’d already impressed British audiences with a refined TV performance on Ready, Steady, Go! the previous year. But now, faced with the raw intensity of the Revue, he knew he had to bring a new level of fire and kick Sam & Dave’s ass.

“Then came the guv’nor—Otis Redding”

- Nick Jones, Melody Maker

“Then came the guv’nor—Otis Redding,” wrote Melody Maker’s Nick Jones, recalling the tour’s first performance at London’s Finsbury Park Astoria. For forty-five relentless minutes, Redding held the crowd in his grip, pouring every ounce of sweat, soul, and stamina into a performance that left him utterly spent.

Redding, exhausted and sweaty as if he left a cage match, muttered off-stage, “I never want to have to follow those motherfuckers again.”

When Redding took the stage at the Olympia Theatre in Paris on March 21, 1967, his wide smile was a signal that the showdown had begun.

WATCH OTIS REDDING PERFORM IN PARIS

In Oslo, Norway, within minutes of Sam & Dave taking the stage, the music cast a spell over the audience. Fans leapt from their seats, danced wildly in the aisles, and stood mesmerized by the duo’s raw power and slick choreography. The excitement spilled over, forcing security to pause the show and issue a stern warning: if safety concerns continued, Sam & Dave would be barred from returning. Their 1966 hit, “Hold On, I’m Comin’,” fueled a storm of sweat and adrenaline, and it was clear—they had stolen the night.

LISTEN TO “HOLD ON, I’M COMIN’” BY SAM & DAVE PERFORMING IN OSLO

“The Stax-Volt Tour gave us a new insight to what the world really thought of us, ‘cause we didn’t think outside the block we lived on,” said Steve Cropper. “But all of a sudden, we got a sense that the whole world is listening to what we’re doing.”

For countless concertgoers, this was their first taste of the Memphis Sound—and by night’s end, they weren’t just converts, they were shouting, swaying, and sweating like they’d been born into it.

Otis Redding. Illustration by J.D. Humphreys

• MARKETING BLACK SOUTHERN SOUL POWER •

Al Bell, then executive and co-owner to Stax, remarked about the “whole man” treatment he experienced in contrast to the country he came from where skin color was made to matter in all facets of life. “It was amazing to have all-white audiences, standing room only, and to be treated by the bellhops or attendants at the hotels and other people like stars. We hadn’t felt that or experienced that before. Although the music came from an integrated group of people, Europeans viewed it as Black’s music, as a music that came from a culture. I realized, the world says this is a legitimate, authentic music, and it should be respected and appreciated as a music of that Black peoples’ culture. That’s what I felt and understood in Europe. And that caused me to move to another level in my thinking of how we would promote and market our product in America.”

“It was amazing to have all-white audiences, standing room only, and to be treated by the bellhops or attendants at the hotels and other people like stars.”

- Al Bell, Stax executive and co-owner

For Bell, this mindset was more than idealism—it was a deliberate business and social strategy designed to break down barriers and bring Stax’s music into mainstream, predominantly white retail markets. The eye-opening experience in Europe confirmed what Bell already suspected: Stax had a sound with the power to resonate far beyond its traditional Southern base.

Bell understood that expanding Stax’s reach wasn’t just about sales—it was about earning broader appreciation for its artists back home in America. Historically, Stax’s records had strongest sales in the South and along the Mississippi River, while markets in the Northeast and West Coast remained comparatively untapped.

Recognizing these patterns, Bell identified Chicago as the crucial “breakout” market—a cultural and geographic bridge between Memphis and the wider world. He dubbed the connection between Chicago and Memphis the “Mississippi River Culture,” a nod to the shared social and cultural currents flowing through the region, and a strategic awareness of the sensitivities needed to successfully expand Stax’s influence.

“My approach to marketing,” Bell said, “was and still is looking from a sociological standpoint. If you appreciate the cultures and what the rivers represent to the cultures in this country, and the kind of music that Stax was coming up with, it would just be logical to look for exposure along the Mississippi River. It was Mississippi River Culture as far as music is concerned. Chicago may as well have been in the suburbs of Mississippi.” Once a record gained traction in Chicago or Detroit, Bell could capitalize on that momentum to push it further into the East and West Coast markets. This strategic approach was key to transforming Stax from a regional powerhouse into a truly national label.

The British Invasion cast a brilliant light back onto the deep-rooted music of America—echoes of soul and rhythm that had quietly pulsed beneath the surface, waiting patiently to awaken the wider world.

“Until the Beatles exposed the origins, the white kids didn’t know anything about the music. Now they’ve learned it was in their backyard all the time,” said Muddy Waters to Time in 1967.

“Until the Beatles exposed the origins, the white kids didn’t know anything about the music. Now they’ve learned it was in their backyard all the time.”

- Muddy Waters